When I think back to many of the unique places I’ve had the opportunity to visit, more often than not it was a horse that led me there.

In anticipation of my upcoming Gobi Gallop ride in Mongolia (more on this later), I thought it would be fun to look back at a few other adventures I have experienced, all thanks to my love of the horse.

Delaware

Ok, I know what you are thinking… Delaware? The “Small Wonder” state? But hear me out.

When I was member of the US Pony Clubs, I was invited to be a Visiting Instructor at a Pony Club camp in Delaware. I was perhaps 20 at the time, and the short flight from Boston was the first one I ever took on my own. I hadn’t flown very much at that point in my life, and so that solo trip was a pretty big deal.

That first USPC Visiting Instructor experience led to others in subsequent years—Oklahoma and Kansas, even California and Hawaii. I don’t know if I’ll ever love flying, but I became more confident about it, and it was all thanks to these trips. In fact, these experiences are probably what made me brave enough to try bigger adventures, like a summer study abroad in Kenya, and later, solo trips to Morocco and the Galapagos Islands.

I have stayed involved with USPC, and through the various roles I have held with that organization (examiner, clinician, regional instruction coordinator, district commissioner), I’ve had the opportunity to travel quite literally from coast to coast. Over the years, Pony Club commitments have brought me to 25 of the 50 states! I am currently on a quest to visit all #50by50…and I only have a handful to go. If you happen to be in need of a clinician– and especially if you live in Texas, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, or North Dakota—don’t hesitate to reach out!

Iceland

Early in my writing career, I produced quite a few breed spotlights. They’ve fallen a bit out of favor with most equestrian publishers these days, but in the late 90’s, I profiled everything from Spanish Normans to Friesians to miniature horses. One time, my editor asked me to pen a feature on the Icelandic Horse—and something about this hardy and unique breed simply captured my fancy. I wanted to ride one, and of course, the only logical place to do so was in Iceland.

I found a company online called Íshestar, and booked an all-inclusive riding tour package. After flying overnight into Keflavik International Airport, and catching a bus bound for Reykjavik, Iceland’s capital, I arrived at my guesthouse to find the owner solidly sleeping off the previous evening’s celebrations. It took a bit of convincing to coax her out of bed to let me in at the ungodly hour of 9 AM—at which time jet lag caught up and I also promptly took a nap.

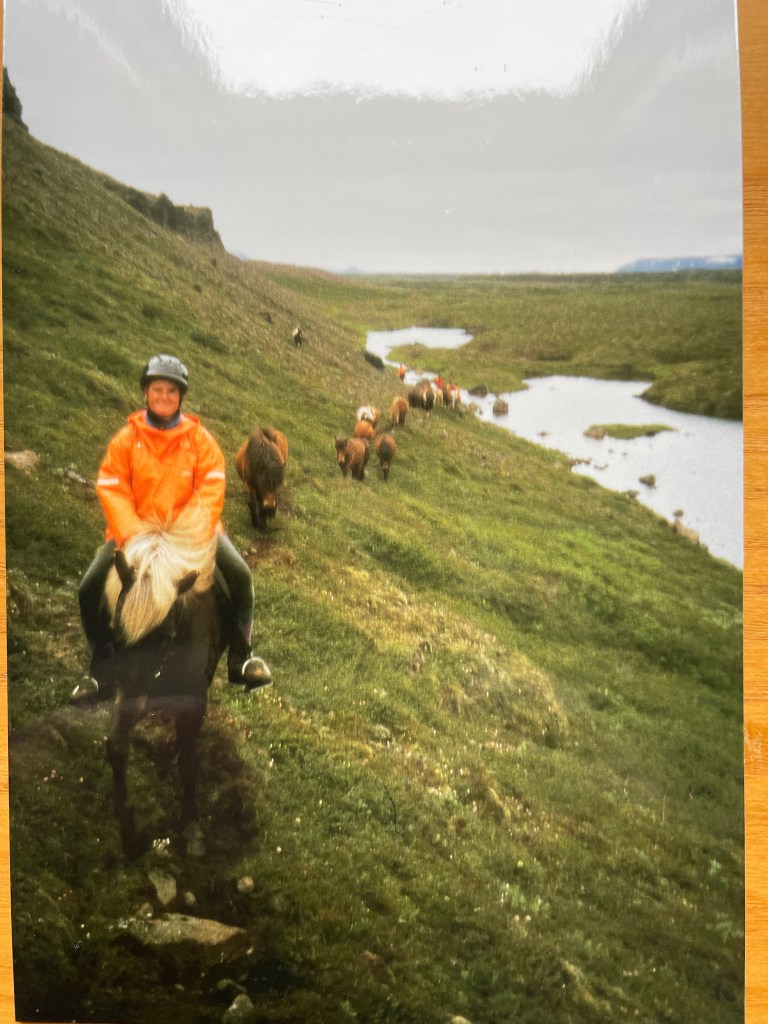

To ride an Icelandic Horse, one must essentially unlearn every skill one has ever practiced on horseback. To slow down, you tip forward. To go faster, you lean back and hold the reins more firmly. One afternoon early in the tour, me and my new Swiss friend Gabi were run off with across a lava field. It took every conscious brain cell I had to not revert to instinct in order to regain control of my rogue mount (who I would later learn had only been “lightly backed”).

Iceland is not a large country, and its people are both friendly and worldly, despite what might seem like a relatively isolated existence on the edge of the Arctic Circle. Our riding tour left from a farm called Saltvík, which is situated on the north side of the island near the city of Akureyri. On the domestic flight up there, we met two young men who knew exactly where we were going and who we would be riding with once we arrived. They wrote their names and phone numbers on an anti-nausea bag, so we could look them up later (we didn’t take them up on that, I’m afraid).

After riding with a loose herd of spare animals over miles of jaw-dropping terrain—including sweeping meadows and volcanic detritus—I have immense respect for the ruggedness of the Icelandic Horse. More than one time, I looked at the trail ahead and thought, “We can’t possibly be headed that way” …and then off we went. They are truly amazing creatures.

If you should ever find yourself in Iceland, one tip—never call them ponies (although strictly speaking, most are well below the 14.2 hand threshold). The reason is, and I quote—“Men do not ride ponies.”

The Mustangs of the High Sierra (California)

At some point, one of my email addresses became subscribed to the University of California-Davis extension course catalogue, and every year, one of their offerings caught my eye. “Mustangs: a Living Legacy” was a four day horse-packing course, co-led by veterinarian/professional horsepacker Dr. Craig London, and extension veterinarian/professor, Dr. Janet Roser. Participants would ride and camp in the Montgomery Pass Wild Horse Range on the Nevada/California border, enjoy lectures and readings on mustangs and the region’s ecology, and hopefully, view the local mustang herd from horseback. It sounded utterly appealing—but with just one annual offering, logistically tricky.

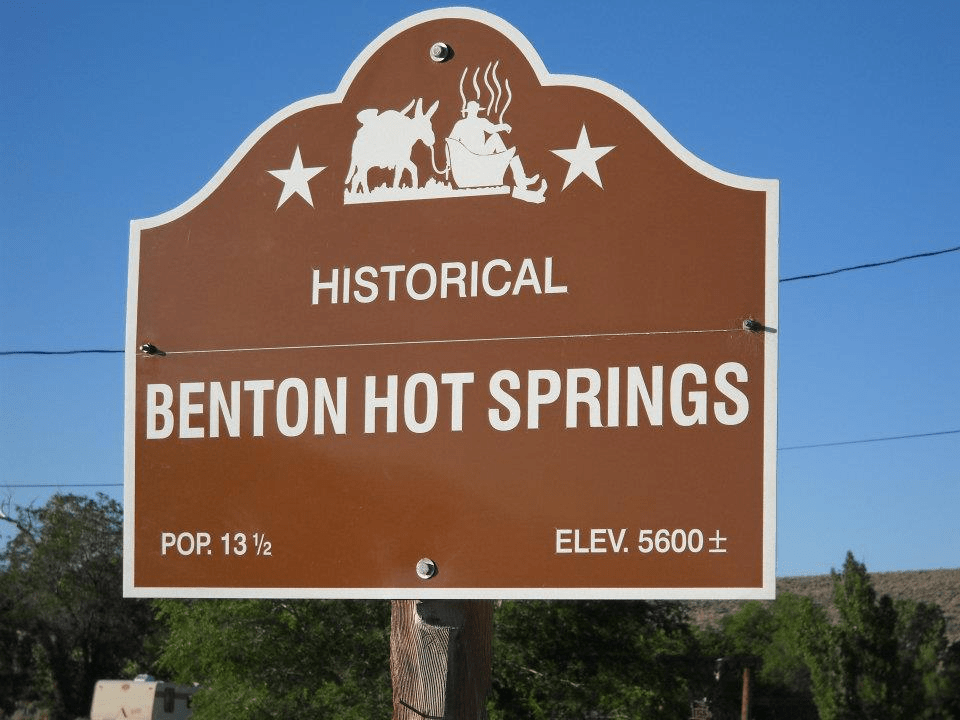

But then one year, the stars aligned. I had a meeting to attend in Las Vegas, Nevada, that was scheduled to conclude just a few days before the start of the annual “Living Legacy” course. I rented a car and drove five hours from Las Vegas to join my fellow mustang enthusiasts in Benton Hot Springs, California (population 279, and that might include the quail).

Partnered with a former county sheriff’s horse named Thunder, I had an amazing experience riding in the high desert of late spring. As I had in Iceland, I gained new appreciation for how well horses handle even some of the most rugged terrain. Additionally, every equine on Dr. London’s horsepacking string tied, and tied well (if they don’t–they don’t last long on his string). We rode for several hours at a time; when we needed a break, the horses simply tied to the nearest tree. Thunder knew the drill and would almost immediately close his eyes and take a nap.

The Montgomery Pass mustang herd was, at least at that time, beloved by the local community, who seemed proud to have them living nearby. The herd was also famous for being one of the only naturally managed mustang populations, thanks to the area’s resident mountain lions. However, as their name implies, mountain lions tend to stay in the higher elevations, and the horses had gotten wise. With ample food and water available on the lower elevation Adobe Flats during the spring, herds could avoid predation.

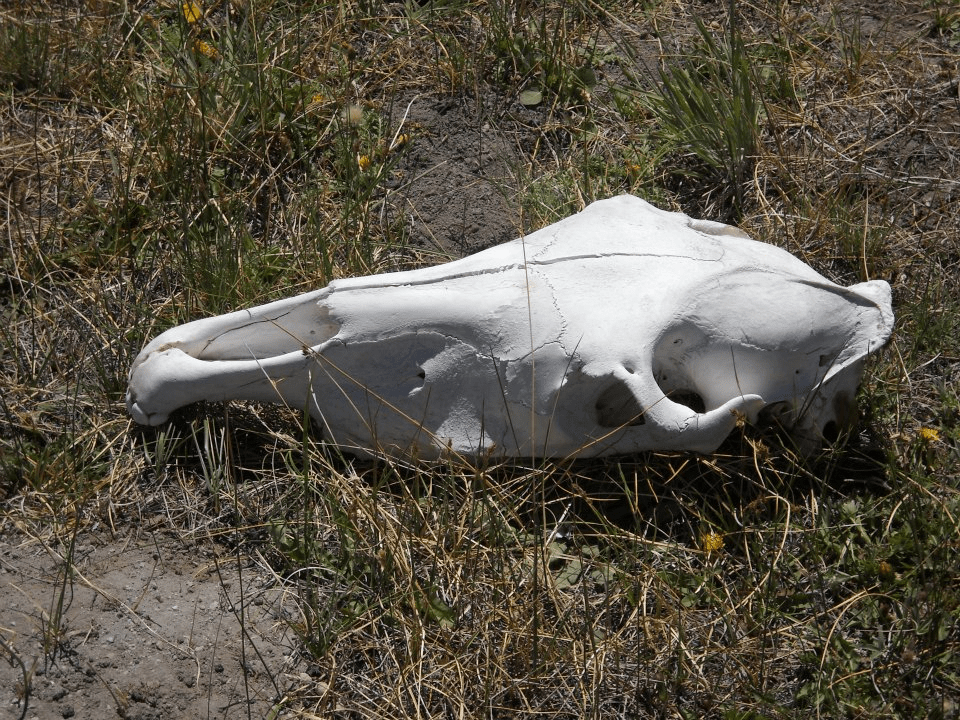

According to local residents, the mustang population was growing every year; I estimate there were at least one hundred animals, perhaps more, when I visited in 2012. Early June in the high desert is still a time of abundance, but it was clear to me that the animals rate of consumption would quickly exceed the vegetation’s capacity to grow. It seemed clear to me that this herd was no longer being “naturally managed”, at least not by the mountain lions. (As a sidenote, in preparing this blog, I reviewed a 2021 article stating that the Montgomery Pass herd population has grown so tremendously that they are now pushing westward, into Mono Lake, California, where they are damaging fragile and unique habitats in their constant quest for food and water.)

As a native northeasterner, studying the dynamic issues surrounding the mustang populations of the west was eye opening, and witnessing firsthand the power of a massive herd as it turned as one unit to flee, emotionally inspiring. Thanks to the influence of UC-Davis, we benefited from peer-reviewed information and objective analysis of the situation; the inclusion of local ranchers and other residents in our conversations helped put a human face on the people impacted (both positively and negatively) by the mustangs’ presence.

In 2012, the Montgomery Pass herd looked to be fairly healthy and in good weight; seeing mustangs in this condition could easily make one skeptical of arguments that many of these animals lead a marginal existence. But after the program was over, and I was heading back toward Las Vegas, a small band of five mustangs (including one scrawny foal) crossed the road in front of me. These animals were painfully thin, and moved with care and deliberation over the flat, rock-strewn terrain. As far as I could see in any direction, the area was fairly barren, the only vegetation small clumps of sagebrush. They seemed oblivious of me and my rental car; as I watched them move away, single file, the shimmering heat made their image begin to dance and wave, until they simply disappeared from view.

The Gobi Gallop—Mongolia

And now, for my newest adventure— the world’s longest charity horseback ride, Mongolia’s Gobi Gallop! If all goes according to plan, I will travel to Asia in late May to join intrepid equestrians from around the world for this ride’s 10th anniversary, all in support of the work of the Veloo Foundation.

The following sentiment, excerpted from the ride’s Facebook page, summarizes one of my main motivations for wanting to participate:

“[The Gobi Gallop is] a chance to see Mongolian horsemen and women from the oldest unbroken horse culture on the planet managing the horses to go 700+km in 11 days…10 days of riding and a rest day. It’s like stepping back to when horses were the only means of transportation, and covering ground like our forefathers.”

But equally important is that my participation in this ride will directly benefit some of Mongolia’s most vulnerable citizens—the children of impoverished families living in Ulaanbaatar, the country’s capital. For generations, many of these families herded livestock on the Mongolian steppe, but modern day challenges combined with an increasingly harsh climate have made this traditional lifestyle more and more untenable. In Ulaanbaatar, these families eke out an existence rummaging through the local dump. The Veloo Foundation’s Children of the Peak Project runs a kindergarten to offer their children a safe place to learn, to grow, and to be mentored. It gives hope for a better future.

Mongolia is the land that gave rise to Genghis Khan (Chinggis to the locals), whose small population of mounted soldiers eschewed hand-to-hand combat and still managed to conquer lands covering modern-day China and Russia, as well as most of the Middle East, the Indian peninsula and as far west as Hungary and Poland. Later, his descendants would cause China’s Ming Dynasty emperors so much worry they would erect a structure now known as the Great Wall. Mongolians were and are master horsemen; their children learn to ride as toddlers, and the horse is fully entwined in the fabric of their nomadic history. It would be safe to say that without horses, Mongolia wouldn’t be…Mongolia.

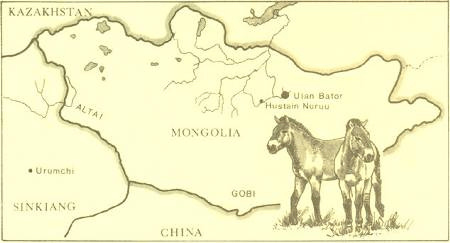

While there, I also plan to make a quick trip to Khustain National Park, home of the wild takhi. The story of the takhi could fill its own blog, but suffice it to say they are the only remaining truly wild species of horse in the world. You might know them better as Przewalski’s Horse (named for the Polish explorer who “discovered” them in 1878), and for many years they were essentially extinct in the wild. But thanks to a captive breeding program located two continents away, the animals were successfully reintroduced, and now thrive on their native steppe.

I am covering all my personal ride expenses out of pocket, and am still actively working to meet my ambitious fundraising goal of $10,000—100% of which benefits the work of the Veloo Foundation. I am just over halfway there, with only weeks left to go—if you are so inclined, please consider making a tax-deductible contribution to my ride! Truly, every little bit helps.

Ok, it’s your turn now—where have horses taken YOU? Or where would you like them to? Drop a comment here! Perhaps you will inspire me for my next adventure….