The musical freestyle is by far the most accessible display of the sport of dressage; even non riders can appreciate the harmony, joy and majesty of the horse and rider partnership when it is set to music. A well-designed freestyle is truly a work of art, melding athletic performance with creativity in ways limited only by the rules of the USEF or FEI.

The Equestrian Center at Pineland Farms (the facility itself is a thing of beauty) in New Gloucester, ME, hosted a continuing education weekend for judges focused on the musical freestyle on May 30-31, 2015. Led by longtime USDF Freestyle Committee member and Klassic Kur founder Terry Ciotti Gallo and supported by USEF “S” judge Lois Yukins, day one of the clinic covered in comprehensive detail a system by which judges can objectively assess the elements on the artistic side of the scoresheet.

This program is just one of several being offered across the country; the goal is to help to create a more consistent standard of evaluation for the freestyle by giving judges an objective method of evaluating a subjective performance. In addition, it is hoped that riders will be inspired to work towards the creation of better, more effective freestyles—or perhaps even to try it out for the first time!

In this blog, I will review the elements of the artistic impression score, as considered by the judge. Information about creating a freestyle, the focus of clinic day two, will be handled separately. There was so much content shared over this weekend that it is simply too much for one article!

Five Categories of Assessment

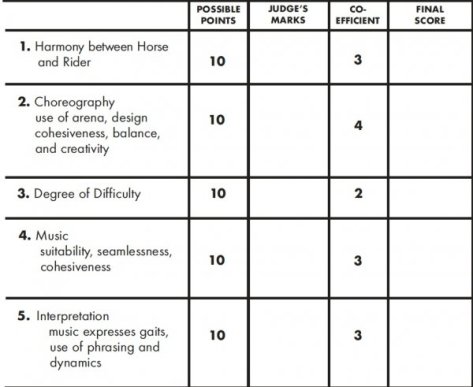

For the USEF levels, there are five categories of assessment on the artistic impression side of the musical freestyle scoresheet. They are (in order on the scoresheet):

- Harmony between horse and rider

- Choreography (design cohesiveness, use of arena, balance and creativity)

- Degree of Difficulty

- Music (suitability, seamlessness, cohesiveness)

- Interpretation (music expresses gaits, use of phrasing and dynamics)

For FEI freestyles, each category has a coefficient of 4 (and they combine music and interpretation into one mark, and add a category for rhythm, energy and elasticity), but for the national test levels, the coefficients vary. Understanding that the biggest coefficient score will come from choreography can help riders to prioritize this score over degree of difficulty. While “harmony between horse and rider” might sound like something which should be on the technical side of the scoresheet, it is scored artistically in USEF tests because harmony reflects the “artistry of the rider”.

Understanding the score for “Music”

In presenting the analysis for each category, Gallo chose to begin with music, as this has to do with selection and preparation, factors which are taken care of before the show. This score is the only artistic impression mark which should not be affected by the technical execution of the freestyle, unless a horse is feeling so naughty that they don’t demonstrate their basic gaits. The score for choice of music should not be influenced by the personal likes or dislikes of the judge, but rather by evaluating the suitability, cohesiveness and seamlessness of the music chosen.

Suitability is the most important aspect of the evaluation, and in judging methodology it represents the basic element for the score; the other qualities can modify the score higher or lower. Suitability means that the music enhances the horse’s way of moving, and should fit the character of the horse. Gallo says that a wide range of genres of music can be suitable -dance music, not surprisingly, can work well for many horses- but it must be level appropriate. Lower level horses are going to be overwhelmed by big, powerful music better suited for pirouettes, half pass or tempi changes. Yukins used the analogy of a supermodel that could look good wearing anything, including a burlap sack, but the average woman must more carefully consider cut and fit. Some horses are so expressive, so beautiful, that nearly any music will work. However, for a more average horse or one that is a flatter mover, well-chosen music can elevate the performance. If the musical selection is suitable, the score for the mark should start at a 7.

Cohesiveness is a modifier to the base score for music, and it means that the pieces of music chosen for each gait have a unified feel. This may be due to genre (all one style, like jazz, classical, rock and roll, etc.), theme (an underlying quality or idea, like all Elvis, all children’s music, and so on) or instrumentation (all pieces are played on piano, or with full symphony, etc). Yukins and Gallo both emphasized the importance of not making the theme too hard to understand—judges have too much to analyze during the five minute performance of the freestyle to make more obscure associations. As Gallo put it, when the theme is so obvious that the judge doesn’t have to think about it, the score goes up; she encouraged judges to give the rider the benefit of the doubt if the music seems sort of cohesive but the judge isn’t sure why.

Seamlessness is the final music score modifier, and this has to do with the editing of the music. The music must flow together, with no jarring shifts which disturb the ear. Editing can be done within a song, or between songs, and is needed in order to have appropriate music for each gait. Basic editing can be done with the use of downloadable software or riders can work with professional editors. Abrupt cuts and overly long fades should be avoided, but short fades can be helpful to create smooth transitions between pieces for each gait. Gallo advises against using a fade out on the final center line, preferring instead to end the freestyle with a closing note or chord in the music.

If all three aspects of the music score are done well, the final mark should be above an 8. The mark for music carries a coefficient of 3.

Understanding the score for “Interpretation”

The score for interpretation of the music is largely determined by what happens during the performance itself. Considered in this mark is how well the music expresses the horse’s gaits, as well as if the rider has coordinated movements with the phrasing and dynamics within the music. Getting a good mark for interpretation requires both advance planning and on pointe execution. It also requires the understanding of some basic musical terminology.

The term beat is used to describe the underlying pulse of the music; it is what your foot wants to tap to as you listen, if you are so inclined. In a horse’s gait, the beat is a footfall. Most riders understand that the walk has four beats, the trot two and the canter three (though for freestyle planning it only has one, which I will discuss in my next blog). Rhythm in musical terms is a repeated pattern of sounds, while for the horse rhythm is the timing and sequence of the footfalls. Tempo is the rate or speed of the beat in music or the rate of the repetition of the rhythm for the horse.

In my second blog related to this weekend, I will discuss how knowing the tempo of your horse’s gaits is related to choosing appropriate music.

When you hear each piece of music, its rhythm and tempo should suggest the gait which it is being used for. While neither the FEI nor the USDF require that riders match the beats of the music to their horse’s footfalls, Gallo says that the smart rider will try hard to do so. That being said, it can be hard to stay right with the beat of the music, especially at the lower levels, as the horses here lack the strength to stay off the ground in the new movements introduced at each level (the leg yield at First Level or the shoulder in at Second Level, for examples). Gallo says that music must at least suggest the gait which it is being used for to get a good mark for interpretation.

If the music is well chosen, it will have clear phrasing and dynamics. Phrasing is a musical unit; at the end of a phrase, the music changes in some way. Dynamics relates to the loudness or the softness of the music; Gallo explained that a forte or crescendo of louder music would indicate a bigger movement (like a lengthening or extension) while softer music suggests circles or pirouettes.

To help judges, Gallo presented the minimum requirement of “Six Point Phrasing”. Basically, a rider who demonstrates their initial halt or salute, their first movement change, their trot and canter lengthenings or extensions, their gait changes and their final halt or salute with musical phrase changes should get at least a 7 for interpretation. Judges should try to note each time the rider goes beyond these six basic points and can add to the score accordingly. If the rider executes the six point phrasing and also matches the footfalls to the beat of the music, the score should be at least an 8. If the rider can also take advantage of the dynamics, then the judge should add a few more tenths of a point. The score for interpretation carries a coefficient of 3.

Understanding the score for “Degree of Difficulty”

The degree of difficulty mark is only worth a coefficient of 2 for the USEF tests First-Fourth, and a coefficient of 1 for Training level, for a reason: attempting to add difficulty that results in poor technical execution makes for bad freestyles. Gallo and Yukins both emphasized how important it is to be totally confident that your choreography will work well for your own horse. “Consider carefully,” says Yukins. “Only do what you can do reliably and well.”

Gallo reminded judges that in a freestyle for a specific level, they should expect to see transitions and movements which correlate to the requirements for the highest test of that level; she even suggested reviewing this test before watching the freestyle. It then is easier to evaluate whether the freestyle performance reflected what the judge was expecting to see (“met” expectations for the level) or exceeded them.

One thing which riders need to be aware of is that they cannot use movements “above the level” to increase degree of difficulty. Judges must be mindful of this and deduct 4 points for any above level movements which are intentionally executed. However, there may be movements which are not traditionally included in standard tests that are permissible for that level of freestyle. On the lower left of each scoresheet, there is a list of movements which are allowed for that level; note that some of these lists changed for 2015.

Examples of ways to increase the difficulty include: a movement at a steeper angle than for a standard test at that level; unusual placement of movements (like a shoulder in off the rail or movements on the center line); demanding transitions (like a canter lengthening to the walk on the same line); challenging combinations (such as a leg yield zig zag); reins in one hand; tempis on a broken or curvilinear line; doing greater than the required number of flying changes.

In terms of scoring, a freestyle that matches the basis for the level should receive a 6 for degree of difficulty. If the freestyle matches the highest standard for the level (such as the movements in the highest test), the score should be a 7. The judge can then add to the score for each element which exceeds their expectations.

Remember that the score for degree of difficulty is linked to the quality of the execution. If a rider tries to do something ambitious and does it well, then they will receive both a high technical mark and a high mark for degree of difficulty. Passable execution will result in no deduction but also no credit. However, if the rider tries for something complex and the quality of the performance falls apart, they will receive penalties in several areas.

Understanding the score for “Choreography”

The choreography relates to the “construction of the patterns”, according to Gallo. There are four criteria which fall under this score: design cohesiveness, use of arena, balance and creativity. Of these four, design cohesiveness is the most important and is the basic score.

Design cohesiveness relates to the clarity and logic of the movements used in the freestyle. It does not need to be symmetrical, but the design should never leave the judge wondering, “what was that?”. If there is clarity in design, the score for choreography should start at 7.

Use of the arena is a modifier to the score. The choreography should use the arena in its entirety, distributing movements around the ring. Freestyles which have all the elements at the far end, for example, are not using the arena well.

Balance in this case refers to the relative equality of movements on the left versus right rein.

Creativity is a modifier which many judges and riders think is the main criteria. Creativity is important, and it refers to combining the elements in interesting ways, or using uncommon lines. Creative choreography is imaginative and not test-like. This does not mean, though, that the choreography is brand new/one of a kind/totally unique. “Not test-like” means that the choreography is not like the movement configurations of any tests currently being used at that level. It does NOT mean that a configuration that was part of a test at that level in years past is off the table. Let’s face it—at the lower levels, there are just not that many movements required and there are only so many ways to put them together.

Choreography really is one of the areas in which both judges and riders need to release their usual concerns regarding test riding and learn to think creatively. Transitions should be made with musical phrases, not at letters. The halt and salute can be done anywhere on the center line so long as they are facing the judge at C. Gallo likes doing diagonal lines that end on centerline, which then allow riders to turn in either direction.

Gallo says that the relationship between the execution of the movements and the score for choreography is indirect. Riders must show lateral movements over a minimum of 12 continuous meters (18 is better); trot extensions must be done on a straight line (mediums may be done on a 20 meter circle) and canter pirouettes must have straight strides into and out of the movement. The only time where execution can really detract from choreography is when a horse has a strong reaction and the judge cannot tell what they did. It is also important to make sure than in an attempt to show creativity, a movement does not appear to be ‘above the level’ (haunches in on a diagonal line looks much like half pass, for example).

Understanding the score for “Harmony between Horse and Rider”

Harmony is something which every dressage rider should aspire to, and watching a well-made freestyle in which horse and rider appear to seamlessly dance to the music can give you chills. The score for harmony reflects the trust between the horse and rider, and the horse’s confidence in both the rider and his own ability to execute the demands of the test.

Getting a high mark for harmony requires that the horse stays calm and attentive and that the performance shows ease and fluidity. This is actually another area in which the FEI and USEF differ—the FEI considers harmony to be about the submission to the aids but the USEF considers it an artistic criterion because it goes into the relationship between the horse and rider.

Harmony takes into consideration the challenges of a good freestyle: staying to the beat of the music, aiming for musical interpretation, the extra demands of increased difficulty and the great number of adjustments that riders must make relative to a standard test. To quote Gallo, “judges should truly appreciate and reward a harmonious freestyle”.

Click on the link above for a visual representation of “harmony between horse and rider”.

Tips for Judges

Gallo and Yukins both emphasized that evaluating the artistic impression of a freestyle is not a matter of simply taking a percentage of the technical mark and calling it good. Judges must use the same kind of system by which to fairly evaluate a ride and arrive at consistent scores that they do to judge regular tests. The “L” program teaches learner judges that to arrive at a score, one must use a formula:

Basics + criteria +/- modifiers= score

By using this same methodology, even something seemingly subjective like artistic impression can be evaluated in a more objective manner.

The artistic impression scores are interrelated with each other, but not all of them relate to the technical performance. Harmony and degree of difficulty are directly linked to the quality of the technical execution. Choreography and interpretation of the music are independent of but modified by execution. Only the music score is not affected at all by the execution of the test.

Judges must be mindful of a few critical rules that pertain to freestyles. For Training through Fourth levels, rides have no minimum time but cannot exceed five minutes. Any movements performed after the time ends are not judged, and a one point penalty is taken from the artistic impression score.

Gallo has a few words of advice for judges. First, in regards to “creativity”, it is important to remember that even if a combination of movements has been done before, or is done the same way by a number of riders, it can still receive positive marks for creativity. The idea is to compare each rider’s performance to what is seen in regular tests, not to what is seen in other freestyles. Secondly, Gallo hopes that judges will continue to learn more about using a standardized system to assess the freestyle. She points out that most judges are experts in dressage first, and have had to learn about freestyle after the fact, and so are going to need time to adjust to a new system.

Yukins cautioned that the judge’s comments on artistic impression are really important, as they will help to shape the future of freestyle. She reminded participants that the role of the judge is extremely difficult, as they have so much to consider. “Judges have six minutes to evaluate a product which riders could have been working on for years,” says Yukins.

Gallo suggests that judges practice their freestyle judging skills by utilizing videos on You Tube. Judges should work to develop a note taking system which allows them to keep track of phrasing and other artistic elements without losing track of the technical score. Another technique is to create a personal “cheat sheet” which can help the judge to keep track of the various elements.

Next up: Creating a Musical Freestyle: Tips from the Top

![The lead pair of a six horse hitch of black Clydesdales. By Blodyn (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://christinakeim.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/black_clydesdales.jpg?w=474&h=356)